This week, Brendan chats to special guest, Dr Charlie Easmon, Public and Occupational Health Specialist about his storied career in international medicine, the BLM movement, his working from home care tips for body + mind and how to protect yourself and others during this time.

Brendan: Hey Charlie, tell us about yourself?

Charlie: So, I’ve been a medical doctor since July 1984. I wanted to be a doctor from the age of five and I had no plan B. I was lucky enough to get into medical school at St. George's. I did my junior doctors jobs and also worked in casualty. I travelled extensively through Australia. Having got back to England, I got very tired and overworked and I finally decided to seek an alternative type of medical career. For six years I became a medical evacuation doctor. So I travelled all over the world picking up sick Brits, which was an amazing, engaging experience. Then I decided I would study public health, which I did at the London School of Hygiene, Tropical Medicine. And then I went to Liverpool to further study tropical medicine.

Brendan: Can you tell us about your experiences working abroad?

Charlie: I did aid work and in Rwanda we set up a refugee camp. It was called Merlin, a British version of Médecin Sans Frontières. I also worked for a youth development charity in Botswana. I did two and a half years with foreign office, which also gave me the privilege of inspecting medical clinics around the world. So, I've had the privilege of visiting at least 75 countries around the world. And in many of those, I've engaged with the medical experts there. After that experience, I decided to set up my own business, which I grew quite successfully, but I didn't know enough about business. And after about seven years it went bust, which was the toughest time and the biggest learning point for me. But I think it was good because a lot has changed in my life for the better. After that, I decided I'd run a much smaller medical business, still based in Harley Street. Since the lockdown, I've realised that I'm very happy working from home. I will do more video consultations and just one or two clinical days a week.

Brendan: What or who do you think influenced you at the age of five to be so decisive about your vocation?

Charlie: My mum was a nurse midwife, so that was probably a factor. I never had any sort of relationship with my father [Charles Odamtten Easmon] but he was a doctor. And it turns out that I'm the seventh in line of a generation of doctors. I've got a picture of my great, great-grandfather from 1879 in his graduation outfit from university college. So there's some history there. I suppose ultimately, I thought it was a profession where I could help people, so that was the altruistic motive in my decision.

Brendan: Did you grow up in London?

Charlie: My mother is from Ghana, West Africa. My father is also from Ghana with the mixture of Sierra Leone. My mother came to England after she had me in search of a new life, I stayed in Ghana for two years and then I was brought to England when I was two years old to join her. As a single mother she struggled getting me educated and balancing work. In the end she decided Catholic boarding school was a logical solution, I went from the age of seven to schools in Leicester, Stoke on Trent and Dorset. They allowed her to pay her bills very late and she used to buy me oversized blazers that I would eventually grow into.

Brendan: What was your overall experience of boarding school and Catholic education?

Charlie: I have to say, honestly, overall it was good. I got depression when I was about 13, and I think that was partly from being the only black kid in school - not knowing who I was, not knowing my identity. It took a year of poor sleep and this sort of greyness, to kind of work out who I was and to come out of that. I remember that as a very formative period of my life. I'd say literature was a saviour when I suffered my degree of mental distress. I actually credit Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron for bringing me out of my period of relative depression. And they gave me world perspective. I always owe a huge debt to Father Jack Morris for the interest in English literature that he instilled in me.

Brendan: Being apart from your family and as the only black kid, surrounded by white people who didn’t represent you, how did you discover your black identity?

Charlie: I would say that learning about black identity came much later. My mother didn't teach me her local Ghanaian language, and being at boarding school, I only ever spent a third of my year with her. In my Thirties I was very privileged to find an American author, Adell Patton, Jr. had written a book of which two chapters involved my family. So, I was essentially gifted my family history by an American author. It turned out that they happened to be quite prominent in the history of West African doctors. One of them was the chief medical officer in what was then the West African Colonial Medical Service. The other ended as a Lieutenant in WWII. And his story was quite funny because he was co-opted in as a Lieutenant and when he was discharged they asked him not to wear his uniform when he got off the train in Sierra Leone, because everyone white under that rank would have to salute him. But he refused to do so, he thought, "I fought in this sodding war, I deserve to wear this uniform," and he did.

Brendan: Obviously, that discovery was quite the revelation. And in a way it explains that becoming a doctor is your destiny?

Charlie: It's interesting. I think in life there are a lot of subliminal influences. If you look at medical families generally, they probably are the ones that concentrate on buying their kid a skeleton jigsaw or a this or a that.

Brendan: You have this blended Ghanaian background combined with the finesse of an English education - how do you feel that's impacted you in this era of a growing Black Lives Matter movement?

Charlie: I think the advantages it gives me are; first, I have a platform. Second, I’m a doctor. And third, I have some media presence and I'm articulate and well read enough to be able to put some good arguments down. One of the talks that I'm planning to give in a lot of independent schools is on the history of prejudice; how do we get to a George Floyd moment? I think we all need to be very aware of how we got here. It's not an accident. It's systemic. I think it's really important that we educate people about that and that we challenge the philosophies that lead to further problems. Here in the UK and the US it can be very much anti-poor, pro-extreme wealth. I'm not against business, I'm not against people being wealthy, but I think we have to challenge some of the views that lead to the domination and power of people who refuse to create a fair world for other people. I feel very strongly about that.

Brendan: You have great expertise in pandemics. What are your observations regarding Covid 19?

Charlie: I knew very early on that we were going to get things wrong. And I also knew there'd be a lot of political distortion in this. So, in March I started a ‘pandemic minority report’ - based on the Philip K. Dick novel. You get the majority report, which is what everyone knows, but there needs to be a minority report with an alternative assessment or reading of the situation. So, I did about 50 posts on LinkedIn, which I'm hoping to self publish as a book, and I'm really proud of what I did. I think there were a lot of things that I got right. I predicted ahead of WHO that this was a significant pandemic, that there was clearly airborne spread and that we would need to increase the use of face masks. For me it's been really fascinating because I've been studying pandemics for years, and giving talks on when the next one was going to come. And I also advantaged a lot of my corporate clients, because at the very beginning I said, "it's going to be huge." And those corporations then had the knowledge to make the plans that, in some cases, saved their businesses. It's been very interesting to watch the political manipulation of the situation and also to be aware of how, in some ways, public health has failed the public. Because the issue for the public is about getting messages across, and in many ways we failed to get sensible, easily digestible messages out there.

Brendan: What do you think the main challenges have been?

Charles: If we look at three governments; the UK, the USA and Brazil, they all have a fairly hard right ideology and they are influenced by this idea that government shouldn't interfere too much and that the right of the individual precedes everything. Public health, however, actually requires some draconian actions. So if you're going to get rid of an outbreak of a disease, sometimes you have to tell people: "This is what we need to do - you might not like it - but this is necessary." Public health, in a way, conflicts with this laissez faire attitude to the citizenry. Brazil, I think, is a mess. The US has huge problems, some of which could have been solved a lot earlier.

Brenda: What do you think of the UK’s response?

Charlie: I think we messed up in not closing down major events fast enough. I think we've had a lot of excess deaths because of Cheltenham and because of the football. Even though we could see advice from the WHO and other countries as to what could be done, we were also very disparaging. There was this mentality of what I call British exceptionalism, that we were going to be fine and all the foreigners had got it wrong. It’s not as simple as that. Sometimes you have to learn from other people and admit that you're learning from them for a successful public health outcome.

Brendan: It's been noted that countries with female leaders have been doing better with a more measured, balanced approach. Do you think it's down to gender, or something else?

Charlie: I think it's down to power politics, and it may be down to gender in the sense that, I think we could say that women tend to be better at listening and more collaborative, whereas men tend to be more direct. I think that there's been a lot of issues with people thinking they know the answer when a pandemic is a rapidly evolving situation. You can't always know the answers. Sometimes you actually have to look around and consult with other people, rather than just saying, "we're doing it this way and going out on our own," especially where deaths are concerned.

Brendan: And what do you make of the conspiracy theories and misinformation regarding the origins of the virus?

Charlie: I'm not sure it's relevant because if you look at human history, we've always suffered pandemics. Looking at the last 400 years, we’ve had two to three pandemics every 100 years. So, we were going to get a pandemic whether it was a ‘lab based one’ or not. The lab theory becomes an irrelevance. As long as humans are mixing with animals, and as long as we encroach into new terrain, we will bring diseases to ourselves. Unless we change, that’s a fact of life. The lab adds another level of complexity, at some point there will definitely be a lab based mega virus or problem, but I'm not convinced this is it.

Brendan: Health problems don’t stop for a pandemic and they can be exacerbated by anxiety. What advice do you give to people who are not sure whether they have Covid 19 and are experiencing random symptoms or getting negative test results? How reliable is the testing?

Charles: So, what happens with a new disease like Covid 19, which we now know targets pretty much every organ in the body, is there will be effects that we won’t fully register until much later. Loss of taste, loss of smell, we know about. A good friend of mine suffered severe tiredness and lethargy afterwards. So we know these things can happen. I think the debate around testing is complex. We can test for antigen and for antibodies. Now, antigen will tell you that the virus is present at the time that you're tested, but all you're doing is taking a swab to specific parts of the throat and the nose. So you may, on that particular day, not capture the virus that is actually there. You're going to have a percentage of false negatives where the person has the infection, but it isn’t picked up from that particular swab. So that's an issue. In terms of antibody tests, it's a little bit more complex. We know that some people don't produce antibodies at all, even though they were clearly infected. We also know that some people, after producing antibodies, the antibody can disappear after a period of a few months. So depending on the window you test them, you may or may not find antibodies. We've tried to provide as much information to the public as possible through a website called covid19check.uk. So we can act as consultants to people who want to ask those more difficult questions.

Brendan: There's little clarity given the complexity of the virus, how long will it be for a vaccine and how successful it will be. The messaging from the government has not been clear. So, how can we, as individuals, protect ourselves and others?

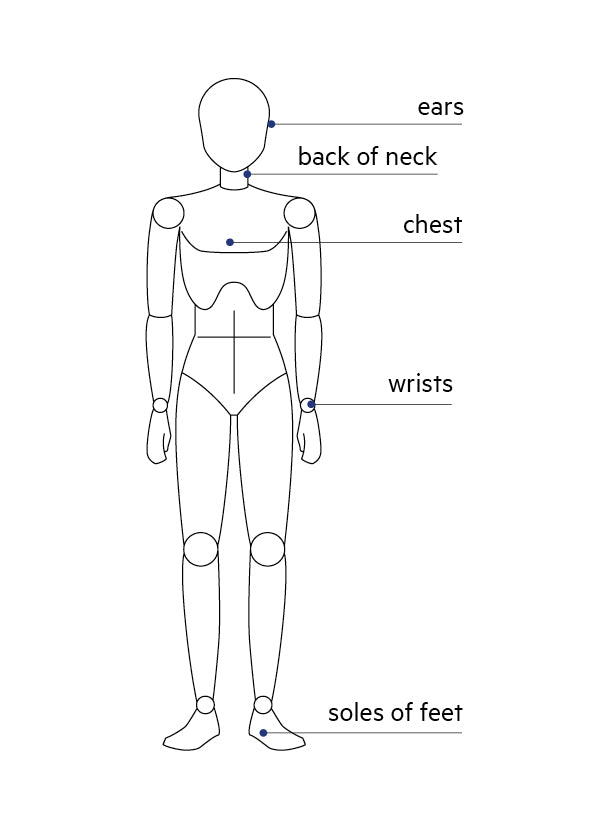

Charlie: I think the key is still to be wary about social gatherings. Limit your network to a few at a time and use a form of mask or face covering. The thing I find most useful is a sort of snood, I've got one here, where you wear it around your neck, and all you have to do is lift it up to cover your nose and mouth when needed and that saves always having to carry a mask. Some of these are washable or are impregnated with silver and can prevent the virus from propagating in them. I would maintain all the rigid advice about hand washing and the use of hand sanitisers with at least 60% alcohol content. We’re in a new era where hand cleaning, using gels and face coverings is going to become routine for a long time actually.

Brendan: It’s summer and people are thinking of holidays and travelling. Do we have to restrict our travel as responsible citizens? What do you think is the sensible approach here?

Charlie: I think we all need some sort of holiday or break for sanity. So, I think somewhere like France is a great idea because you can reduce your overall exposure by driving and you're not going to mix and mingle a lot when you get there. Where I would be wary, is going on a trip to a packed resort with a bunch of people who are knocking back pints and bundling over each other - because that's almost certainly going to cause a problem. I think a holiday is fine, just be cautious of where you go in terms of how much you expose yourself to other people who may be out of control.

Brendan: Isolation can be harder for some than for others. What steps do you take to protect your own mental health and what advice do you give to your client base?

Charlie: One of the things to do in lockdown or in any form of isolation is to break up the day. So you need to do some exercise, at least three times a week, and it should be at least 30 minutes of heart-pounding, hard to breathe, aerobic exercise. The danger of working from home is you could be working till midnight every night if you’re under pressure. I would set a timer and do 40-minute sessions instead of long sessions. And at 40 minutes, allow yourself a break - read a book, watch a quick video, or just have a cup of tea. At a certain point in the day, it's cut off time and I'm not working anymore and I'm not looking at my emails, because this is my time. Take control over your break periods.

Brendan: What advice do you give to parents whose kids still need to socialise?

Charlie: I think this is a really difficult situation. One of the books I'm writing currently is a guide for parents for their children's mental health. Personally, I would allow kids the chance to play in the park. But I think every parent has different levels of caution about whether they want their child to mix with other children. And I think that's a parental decision that you have to take. I don't think you can put a five-year-old in a situation where there are lots of five-year-olds happily playing and expect them not to mingle. If you’re not comfortable with that, then you have to make a decision.

Leave a comment